Sound Manufacturing with Frankie Benevides, Jr.

Intro and Interview by Nick Ferreira

Photograph by Jared Souney

Growing up in New England, I was lucky to have access to not only a great riding scene but the bike shop Dick Maul’s. Maul’s was the precursor to the modern boutique BMX shop. While most other shops I went to had a small area of BMX parts, Maul’s was predominately a BMX shop. It was stocked with frames, parts, and clothes from all of the brands I had read about in magazines, but it also had shirts, videos, and zines created by local people in the scene. This focus on the scene was solidified with Maul’s being housed in owner Dick Maul’s garage. It was at Maul’s that I discovered what the local clothing company Sound Manufacturing was via their graphic t-shirts. And then, like so often happens when you become aware of something new, it felt like I couldn’t go to any local park, racetrack, or ramp and not see the classic Sound “stars” sticker. The stickers and clothes were highly coveted among my friends and for me Sound became a seemingly obtainable model of how I could combine an interest in visuals and graphics with BMX. Sound visionary and man at the helm, Frankie Benevides Jr. talked with me to give me more insight into the project.

Challenger:

Can you tell the readers how Sound started?

Frankie:

In the 90s, I didn’t drink. I thought it’d be a riot to wear a shirt that just said BEER across the front in huge black letters. I’d known Stew Johnson for a few years and he was doing Scum at the time, so I just drove from MA out to the Fat House one day in the Spring of ‘96 and he made them for me. Not long after, he stayed with me for a couple weeks in MA before moving to Bethlehem. He sold me his press, so I started coming up with designs and just went at it.

Challenger:

So the Scum press became the Sound press? How did you know Stew? Were you Stew’s Massachusetts connection?

Frankie:

Yes, the sound press was the Scum press. In 1992 randomly moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana after I graduated high school. The guy I moved there with ended up engaging in some pretty serious criminal behavior and I didn’t want to be around it. I had met Stew at the local skatepark and we hit it off, so I asked him if i could stay with him for a bit until I could figure stuff out. I ended up moving back home to Massachusetts about three weeks later.

The guy I originally moved there with got arrested, as did everyone that lived there [in that apartment I lived in] because he was storing everything he stole at the apartment. I got out just in time. Stew and I kept in touch and I went out there a bunch. It was then the Fat house happened and Joe Daugirda was part of that, so I wasn’t the only MA connection.

Challenger:

One thing that still sticks out quite a bit is that Sound was very thought out, even by today’s standards. When we were recently talking you told me you even wanted the catalog to be a “product” that people collected. I think that worked; I still have that catalog. It feels kind of weird to ask this question but why were you so focused on having that level of thought go into the project?

Frankie:

I’d tend to hold on to tons of shit back then. I’d occasionally purge, but there were always things I’d keep and I’d always think a lot about why that stuff held personal value. I enjoyed objects that had obvious thought behind them and that was what I wanted to create. Honestly though, I just didn’t know how else to do it. I needed to create stuff that people would cherish. I definitely missed the mark sometimes but I was lucky enough to realize they were just iterations, not failures.

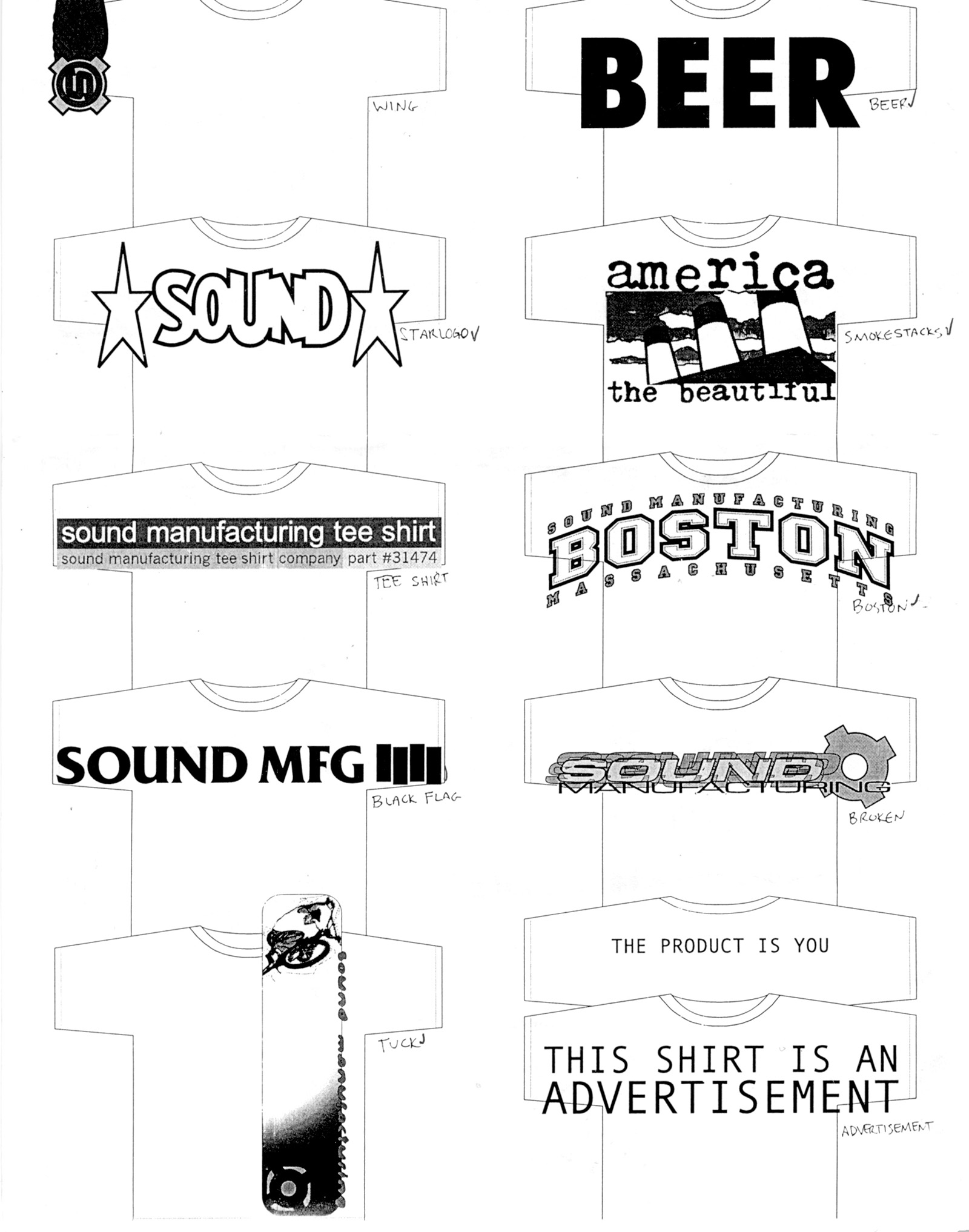

![]()

Sound T-Shirts from c. 1998 Catalog

Challenger:

Was Sound ever something that you lived off?

Frankie:

I wouldn’t say I lived off it, but there was a little while that screen printing was the only job I had. I’d print stuff for other people too like Scum, T1, and local companies, and that’s what paid my bills at the time. Mostly Sound was a way for me to just meet more people and make cool shit.

Challenger:

You were a big proponent of the web in earlier days. What potential did you see in the web and do you think that potential came true?

Frankie:

It was obvious that anyone with a computer had an instant worldwide audience. Shopify and Etsy are perfect examples of what I’d hoped for, but my vision wasn’t unique. What scared me was how easily communities could devolve into toxicity. I experienced that pretty early on and it soured me more than I’d admit to myself for years.

Challenger:

There were hints to broader cultural influences in Sound. Besides BMX companies, what were some of your influences at the time you were working on Sound?

Frankie:

Zines. All the zines… holy crap the zines. There was a big Boston zine festival every year that was fantastic and the maker community around it was eye-opening. Music goes without saying. Graffiti was a huge influence, but I don’t think it was very obvious. Magazines like Ray Gun, Adbusters, and Interview were constant inspiration. My friends had more influence on me than anything cultural, though. Without a select few of them, Sound never would have happened. ︎

Challenger:

Can you tell the readers how Sound started?

Frankie:

In the 90s, I didn’t drink. I thought it’d be a riot to wear a shirt that just said BEER across the front in huge black letters. I’d known Stew Johnson for a few years and he was doing Scum at the time, so I just drove from MA out to the Fat House one day in the Spring of ‘96 and he made them for me. Not long after, he stayed with me for a couple weeks in MA before moving to Bethlehem. He sold me his press, so I started coming up with designs and just went at it.

Challenger:

So the Scum press became the Sound press? How did you know Stew? Were you Stew’s Massachusetts connection?

Frankie:

Yes, the sound press was the Scum press. In 1992 randomly moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana after I graduated high school. The guy I moved there with ended up engaging in some pretty serious criminal behavior and I didn’t want to be around it. I had met Stew at the local skatepark and we hit it off, so I asked him if i could stay with him for a bit until I could figure stuff out. I ended up moving back home to Massachusetts about three weeks later.

The guy I originally moved there with got arrested, as did everyone that lived there [in that apartment I lived in] because he was storing everything he stole at the apartment. I got out just in time. Stew and I kept in touch and I went out there a bunch. It was then the Fat house happened and Joe Daugirda was part of that, so I wasn’t the only MA connection.

Sound Manufacturing Promo, 1998

Challenger:

One thing that still sticks out quite a bit is that Sound was very thought out, even by today’s standards. When we were recently talking you told me you even wanted the catalog to be a “product” that people collected. I think that worked; I still have that catalog. It feels kind of weird to ask this question but why were you so focused on having that level of thought go into the project?

Frankie:

I’d tend to hold on to tons of shit back then. I’d occasionally purge, but there were always things I’d keep and I’d always think a lot about why that stuff held personal value. I enjoyed objects that had obvious thought behind them and that was what I wanted to create. Honestly though, I just didn’t know how else to do it. I needed to create stuff that people would cherish. I definitely missed the mark sometimes but I was lucky enough to realize they were just iterations, not failures.

Sound T-Shirts from c. 1998 Catalog

Challenger:

Was Sound ever something that you lived off?

Frankie:

I wouldn’t say I lived off it, but there was a little while that screen printing was the only job I had. I’d print stuff for other people too like Scum, T1, and local companies, and that’s what paid my bills at the time. Mostly Sound was a way for me to just meet more people and make cool shit.

Challenger:

You were a big proponent of the web in earlier days. What potential did you see in the web and do you think that potential came true?

Frankie:

It was obvious that anyone with a computer had an instant worldwide audience. Shopify and Etsy are perfect examples of what I’d hoped for, but my vision wasn’t unique. What scared me was how easily communities could devolve into toxicity. I experienced that pretty early on and it soured me more than I’d admit to myself for years.

Challenger:

There were hints to broader cultural influences in Sound. Besides BMX companies, what were some of your influences at the time you were working on Sound?

Frankie:

Zines. All the zines… holy crap the zines. There was a big Boston zine festival every year that was fantastic and the maker community around it was eye-opening. Music goes without saying. Graffiti was a huge influence, but I don’t think it was very obvious. Magazines like Ray Gun, Adbusters, and Interview were constant inspiration. My friends had more influence on me than anything cultural, though. Without a select few of them, Sound never would have happened. ︎